With The Great War - July 1, 1916: The First Day of the Battle of the Somme, An Illustrated Panorama, comics journalist Joe Sacco has created a single, 24-foot-long gatefold image which re-creates the events of this day of battle across time and space. Surrounded by two hard covers, the gatefold image comes in a slipcase which also includes a booklet with an author's note and annotations by Sacco, as well as an essay ("July 1, 1916") by historian Adam Hochschild.

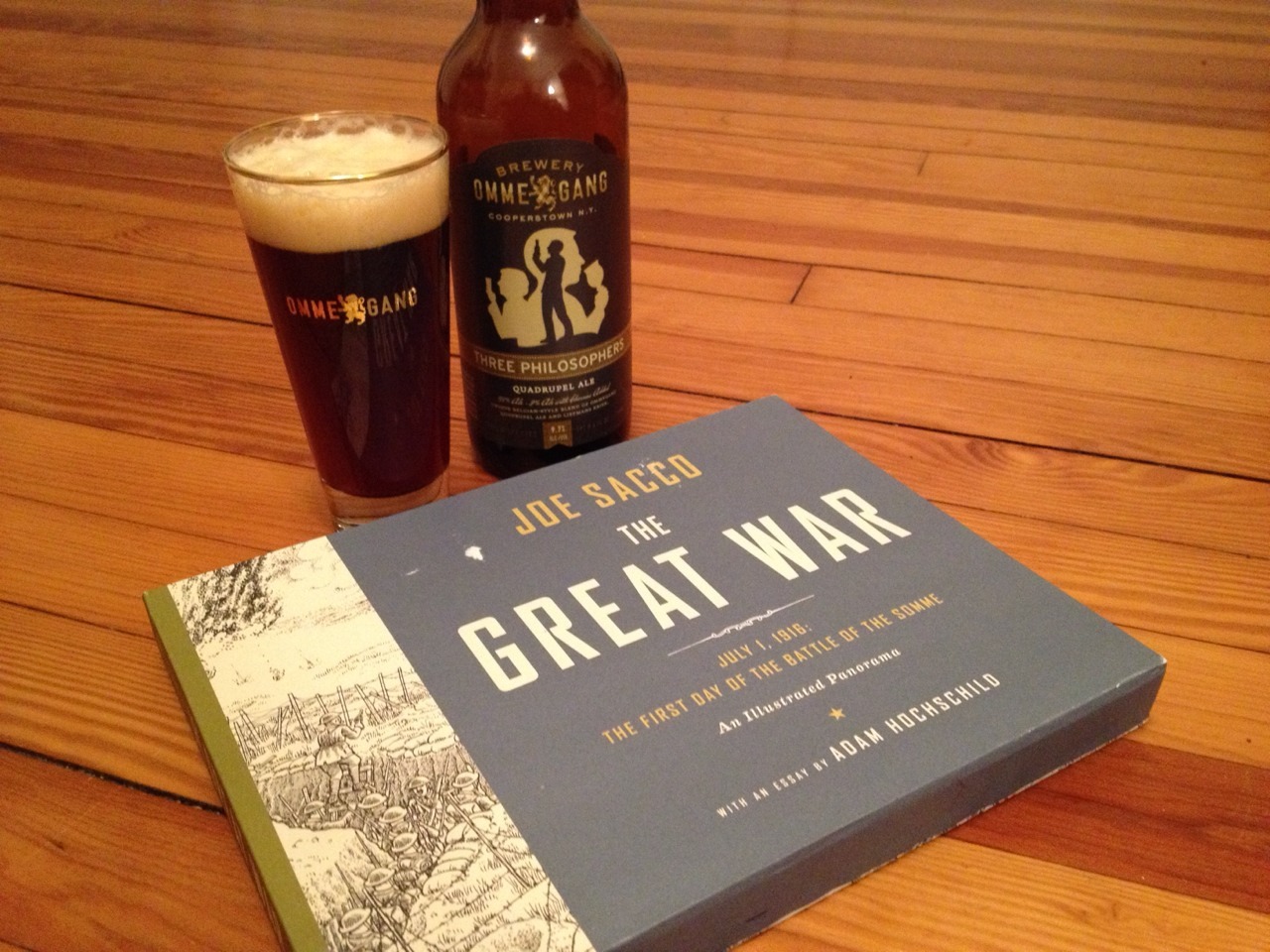

Photo from this New Yorker interview with Joe Sacco.

Technically, Sacco's image is a tour de force, utilizing shifting perspectives to create the illusion of a single image while also presenting a chronological narrative of the battle's stages. The amount of detail Sacco includes is staggering, including scores--no, hundreds!--of soldiers, and mazes of trenches that seem to go on for miles. Explosions, debris, and devastation abound, and the passage of time allows us to contrast the idyllic pre-battle landscape to the horrific aftermath.

I was intellectually impressed by Sacco's artistic achievement, but it is only Hochschild's essay that really devastates on an emotional level. I already knew that the First World War, that horribly mis-named "War to End All Wars," was a ridiculous waste of human life,;but Hochschild's essay covering the myriad details of this particular battle--the blindly hubristic plans, the utterly devastating results--really drives the point home in ways that not even Sacco's massively detailed panorama can achieve.

The artwork is stunning technically, but without Sacco's annotations and Hochschild's essay, I'm not sure how affecting the end result would be. Actually, I do, and the answer is that it would appeal a lot to my eyes and brain, but much less so to my heart. Sacco's image needed to be a part of this complete package; the panorama alone, impressive as it is, is not enough to drive home the point Sacco strives for. Which he himself acknowledges in his introduction:

Making this illustration wordless made it impossible for me to provide context or add explanations. I had no means of indicting the high command or lauding the sacrifice of the soldiers. It was a relief not to do these things. All I could do was show what happened between the general and the grave, and hope that even after a hundred years the bad taste has not been washed from our mouths. ("On the Great War," Author's Note, p. 2)Design-wise, The Great War is an impressive package, even if the panorama itself is an unwieldy read (but how could it not be, unless it were mounted along a wall?). One bravura touch it how the book begins and ends. The first image on what would normally be the front endpaper is a close-up drawing by Sacco of the famous Lord Kitchener WWI recruitment poster, followed by the title page; the rest of the book is the panorama itself, which extends all the way to what would normally be the back endpaper. In that final portion of the image, we see soldiers digging and filling graves. So the design leads us rhetorically from heavily romanticized recruitment to the devastating, utter finality of death. The end.

Make war no more!